We’re pretty used to drones flying around us by now thanks to the ubiquity of IoT. Until now most of these drones were still controlled by a human operator. But what if we could control them solely using our code? At Codemotion Amsterdam in 2019, Jasper Schulte offered a fascinating interactive presentation into how to control multiple drones using Javascript. He spoke about the difficulties of flying and keeping control of a drone completely without human interference. In the second part, drones flew and audience members participated in a small ‘drone’ game.

As this was an interactive presentation, we’re providing an overview but encourage you to watch the video also to deep dive into the code and enjoy the demonstrations!

Step 1: Choosing the right drone

Until fairly recently, drone enthusiasts had to solder and build drones themselves, using microchips to control the drones. Today, there is an abundance of ready to fly (RTFP packages) which basically meant that you get an off the shelf drone. These vary in price, for example, a DJI Phantom will cost about 2000EUR.

Jasper needed drones to be cheap, relatively safe and have an interface for communication and able to fly indoors. Thus, his affordable drone of choice is the RyzeTech Tello. It costs about 100 euros and weighs a mere 95 grammes, and importantly has a UDP interface protocol so you can send messages. It doesn’t have GPS.

Importantly, it has a downward-facing camera. “Internally in the drone, it does visual recognition of the ground, basically just sees the pattern on the ground. As soon as it understands the pattern, it can see the pattern moving. It can keep the drone in place.”

Downward facing camera benefits:

- Visual recognition of patterns on the ground

- Keep the drone in place

- Track distance moved

Step 2 Controlling your drone

Sending commands and receiving telemetry

Jasper explained: “Sending commands is obvious, we need to tell the drone where to go or what to do or what to go up, go down, go left, go, right. And of course, we need to receive telemetry. So if we want to know where the drone is, we need its relative position.

The protocol UDP is the best effort protocol meaning it’s not perfect but it about making a good guess – you send the command to the drone but don’t know if it arrived, is accepted or completed. Thus, you wait a certain amount of time after executing each command ot know that it’s finished.”

Jasper presented a number of coding demos where he literally flew the drone while coding on a laptop. He explained:

“So basically, if we take a look at the code, we start with some imports, of course, are constants with a port with an IP address. We create a client based on the UDP protocol. We have a small helper function just to send commands, which of course accepts a command. And then we log it. And there’s just a small our error handler.

But the interesting stuff is, of course, sending the command. So we have a small programme or a small function here called send, the first thing it will do is it will send a command. because the drone kind of needs to be put in an SDK mode.”

What do we need for coordinated flight?

Controlling several drones simultaneously requires knowledge of where the drones are relative to each other. “So in order for the drones to understand where they are relative to each other, basically you need to know where the drones are in this in a certain space.”

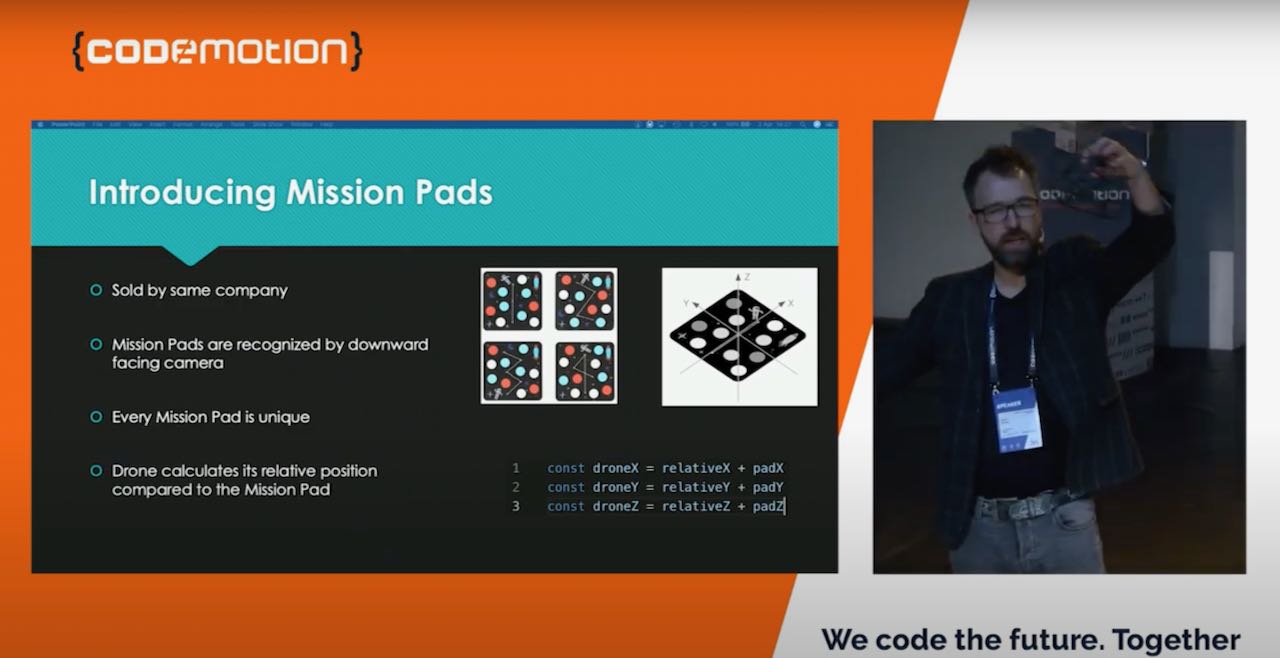

One thing that makes this possible is mission pads:

Mission pads are recognised internally by the downward-facing camera. Jasper details: “So when the drone flies over the pads, it recognises them and it will recognise each individual pad as well. Then the last thing that the drone does is it actually calculates its relative position to the pads. So if I take the drone if I take a pad, and if I move it around, it will kind of know where it is compared to this pad, and the pad will have its own unique coordinates, it will have its own kind of coordinates.”

Tips for flying drones

Jasper stresses: “Controlling drones is hard. This is basically first of all because these are cheap drones so the quality of the sensor inputs is not that great.” Drones rely on good quality light which is difficult to emulate during an indoor presentation so that the drone can actually see the floor, especially due to inferior nature of the sensors. “it’s still a 100 euro drone, and it’s already amazing what you can do for the hundred euros. But you have a lot of external factors.

Down draft can also be a problem: “At first when I was making the drones, drones fly over each other, but then you would get the downdraft of the drones which would kind of push the other drone away and it would not compensate for that so so it’s just hard you have a lot of external factors.”

Jasper notes: “I have to advise you get rid of your cat because they actually attack like they will jump on your drones. Also, get rid of your plants because the drones attack the plants and you’ll get plenty of broken leaves and branches all through your house.”

Be prepared to crash a lot.

One of the big downsides of drone tech is the code on the drone, it’s not open-source, it’s proprietary.

Jasper had a number of next steps planned for developing his drone tech further. He intended to make it lower light tolerant, “as it would be nice if we didn’t have to put So much effort into getting enough light here. I want to move away from the proprietary systems which would be nice so you’re kind of not limited to the eight mission pads. This would also mean you can get an even bigger grid. Therefore, you can get more drones and you can have even more fun.”