Let’s get it straight: it is wrong to have more than one application container inside a single Pod. There are different reasons behind this statement and I will mention just a few of them. In any cases, the way Kubernetes has been designed brings us to the fact that having just one application container per Pod gives us a lot more flexibility.

Two application containers: a bad idea

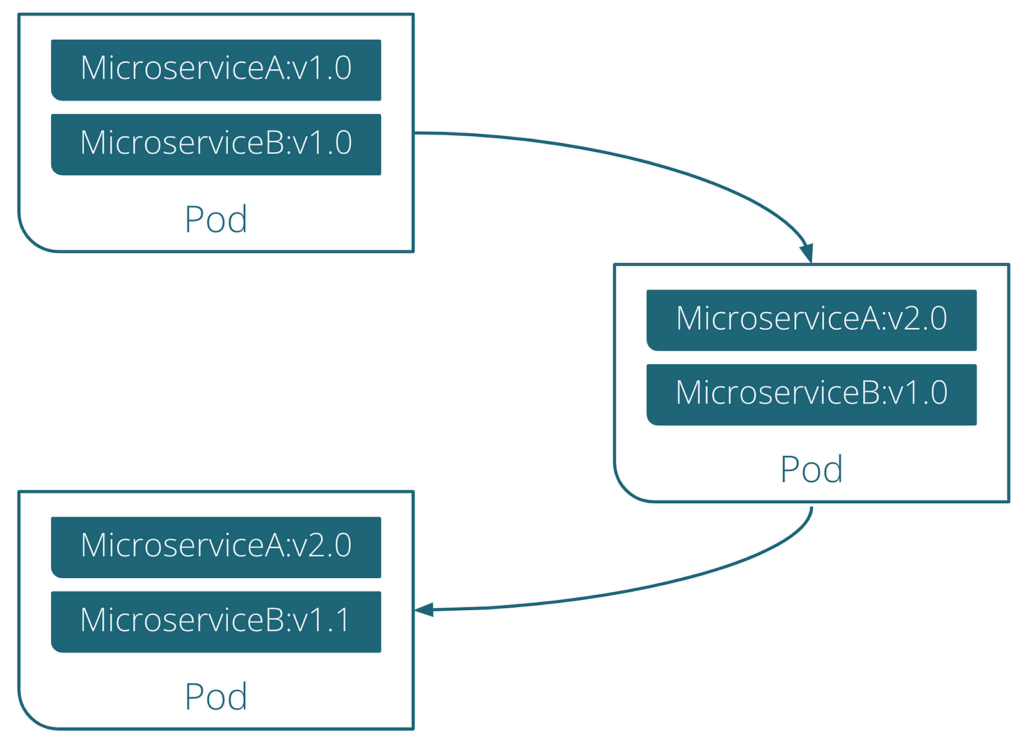

We have an application, made of various microservices. We deploy them using Deployments. In one of these Deployments, we choose to have 2 of our microservices, let’s say Microservice A and Microservice B. The first releases for both microservices are tagged v1.0. Time goes by and we develop a second version of Microservice A, tagged v2.0. We deploy it, and the Deployment now have v2.0 for Microservice A and v1.0 for Microservice B. In the meanwhile, Microservice B’s team worked to bring some minor enhancements, and we can deploy Microservice B v1.1. We update our Deployment and we now have a situation with Microservice A v2.0 and Microservice B v1.1. We update our Deployment and we now have the situation shown below.

While using the application, some of our users reported some serious bugs. We analyze the problem and notice that we must rollback Microservice A to v2.0. We go to our Deployment and… Oh, wait! We can’t rollback without losing Microservice B’s minor enhancements. We must then rollout a new version of our Deployment, containing MicroserviceA:v1.0 and MicroserviceB:v1.1, instead of performing a rollback. That’s definitely not how Deployments are intended to be used.

Just a few more examples:

- Scalability: imagine there is a Horizontal Pod Autoscaler in place. You define that the autoscaler will add new replicas when the CPU consumption of a container reaches a certain threshold. If there are more containers in the same Pod, the autoscale will create new Pods, containing even the containers that don’t need to scale and resulting in an excess of resources consumption;

- Scheduling: just consider Pod Affinity. It is done at Pod level, so it affects every container that is inside the Pod. Or consider that the Scheduler will try to optimize resource consumption: having more containers, and consuming more resources, will result in less optimized scheduling.

Is it then always wrong to have more than just one container inside a Pod? Well, there are some cases when it is rather convenient to use some companion containers, that will help the application container to do its job. What is important is to have only one application container.

When it is right: Sidecar, Adapter, and Ambassador patterns

Having understood that we should have only one application container in a single Pod, it is natural to imagine when it is right to have more than one container: when the other containers serve the main, application container. In which way? Well, the way they serve the application container tells us which design pattern we are using, and we have 3 of them: Sidecar, Adapter and Ambassador pattern. From a container point of view there is no difference: we just have a companion container that performs operations instead of making the application container do them. That is very convenient:

- the application container will not have to do things that are not related to the Business Cases that it resolves, resulting in a good separation of responsibilities;

- we have a modularity that allows us to easily change the companion container without having to change the application one. The containers are loosely coupled and very maintainable;

- having a set of companion containers reduces development time: we can reuse a lot of companions when we have to deal with the same problems.

Sidecar pattern

Think of all those cases where it is necessary to add essential functionalities, such as logging, monitoring, and caching. We could instrument our application, hard-coding those functionalities, or we can just write our code to solve our Business Cases. The companion object will add logging, monitoring, caching and similar functionalities, acting instead of our application, collecting logs and metrics, or caching frequently used datas.

Adapter pattern

Similar to what the GoF’s Adapter Design Pattern can help us achieve, the Adapter pattern allows us to use a companion container to act as an object that translates the communications between the application container and the outside world. We can use it when, for example, we need to communicate with external APIs that use different data structures. Imagine having a lot of these external APIs, and an adapter can translate all of the data structures to the one used by our application. The same goes if we use a message broker to exchange messages: the adapter will translate the messages so the application can process them using just one structure. Whenever you need to bridge communication gaps with external systems, an adapter is the perfect choice.

Ambassador pattern

An ambassador container acts as an intermediary, handling external requests and forwarding them to the application container. We can use it, for example, to enforce authentication and authorization policies before passing requests on to the application. Again, we can proxy the connection between the application and a remote database, providing a secure channel without forcing the application container to enforce the security on its own, simplifying its implementation. The ambassador pattern promotes increased control and agility. It allows you to implement security measures, optimize traffic flow, and manage application instances without modifying the core application container.

Setting up the Pod: InitContainer

There are cases when the companion we need should only prepare the Pod, initializing it for the application. For example, we may need to clone a git repository in the locally mounted Volume, because the application will use the downloaded files. We may need to dynamically generate a configuration file. Or we may need to register the whole Pod with a remote server from the downward API. In these cases, Kubernetes gives us a powerful option: InitContainers.

InitContainers are containers that run to completion during Pod initialization. We can define many of them, and each of them must run to completion before the application container starts. Kubelet will execute them sequentially, one after the other, in the order we define them. They are obviously different from a sidecar or an ambassador, as they will not be a companion. They will just set up the Pod for the application and stop.

We can see an example of the definition of an InitContainer below. Note that SERVICE_INITIALIZATION and DB_INITIALIZATION are a placeholder for a generic command that will perform some initializations.

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: myapp

spec:

containers:

- name: myapp-container

image: myapp-image

initContainers:

- name: init-myservice

image: busybox:1.28

command: ['sh', '-C', 'SERVICE_INITIALIZATION']

- name: init-myservice

image: busybox:1.28

command: ['sh', '-C', 'DB_INITIALIZATION']Code language: YAML (yaml)This is a particular case of having multiple containers in a single Pod: effectively, InitContainers won’t run simultaneously, but still, they will all be executed in the same Pod.

Conclusion

Sidecar, Adapter, and Ambassador patterns, together with InitContainers, are very useful approaches for all those jobs that, instead, would require the main application to change. They provide support for the main container and must be deployed as secondary containers. Which pattern we are using depends on the kind of work that the companion container does. Also, this way we have highly reusable containers for different use cases.

Just remember to not put more than one application container in the single Pod: having a companion is always helpful, but we don’t want to put two feet in the same shoe.