The architecture of microservices seems to be becoming extremely popular among backend applications these days. But what about the frontend side? We can clearly see that frontend applications are growing very fast in terms of business logic and bundle size. Let’s see what can happen if we try to apply the architecture of microservices on the frontend side.

I heard about this concept of micro-apps at the conference Codemotion Amsterdam 2019. The talk was given by Sander Hoogendoorn and it was called “Welcome to the world of micro-apps”.

Did it mean microservices?

Not really. But before we start talking about micro-apps, let’s remember microservices. A few years ago, quite a strong trend started in the backend world; many developers and companies started switching from big monolithic backend applications to so-called microservices.

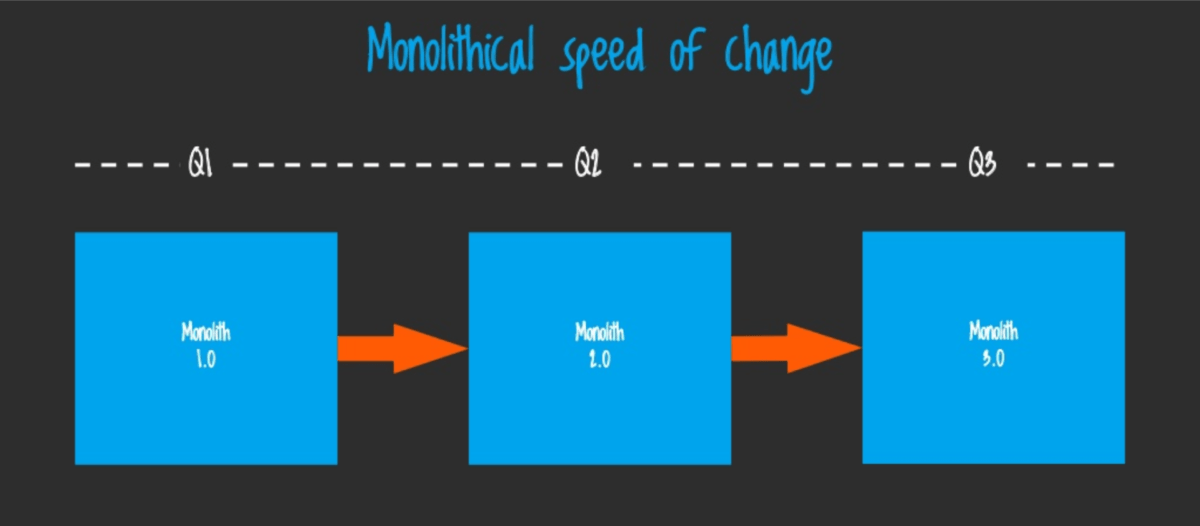

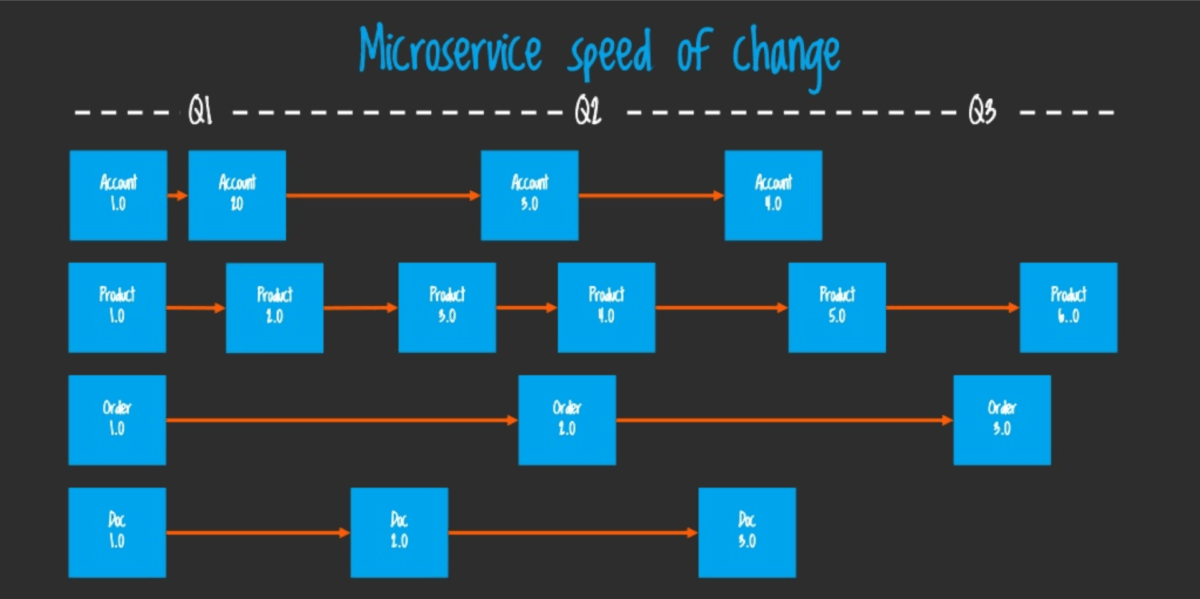

Microservice is a very small standalone application which has very limited scope and responsibilities. It usually has separate storage and can communicate with other microservices in order to get data from another scope. In this case, the frontend application communicates with each microservice directly or via proxy API (gateway). This concept has a number of benefits compared to the monolithic architecture. You can especially notice them in large enterprise projects. For example, it’s getting much easier to test, maintain and deploy each microservice separately and that leads to more regular and smooth releases. RIsk of breaking the whole application decreases as well. If we check the speed of changes, we might end up with something like this for monolith application:

Compared to this situation in the case of microservices architecture:

But at the same time, it becomes more difficult to share common code between the microservices. As always, there is no single right way here, there is a trade-off. Anyway, it’s considered a very common architecture on a backend side nowadays and developers seem quite optimistic about this pattern.

But what do you mean by micro-apps?

If you look at the situation on the frontend side you can see that applications there also become more and more complex and heavy. And it becomes harder to maintain them. Of course, you can say that we have NPM registries where we can publish our custom modules and then use them in projects. It helps, but only partially. For example, you can’t re-deploy only your module to see its changes in production, the whole application also needs to be re-deployed.

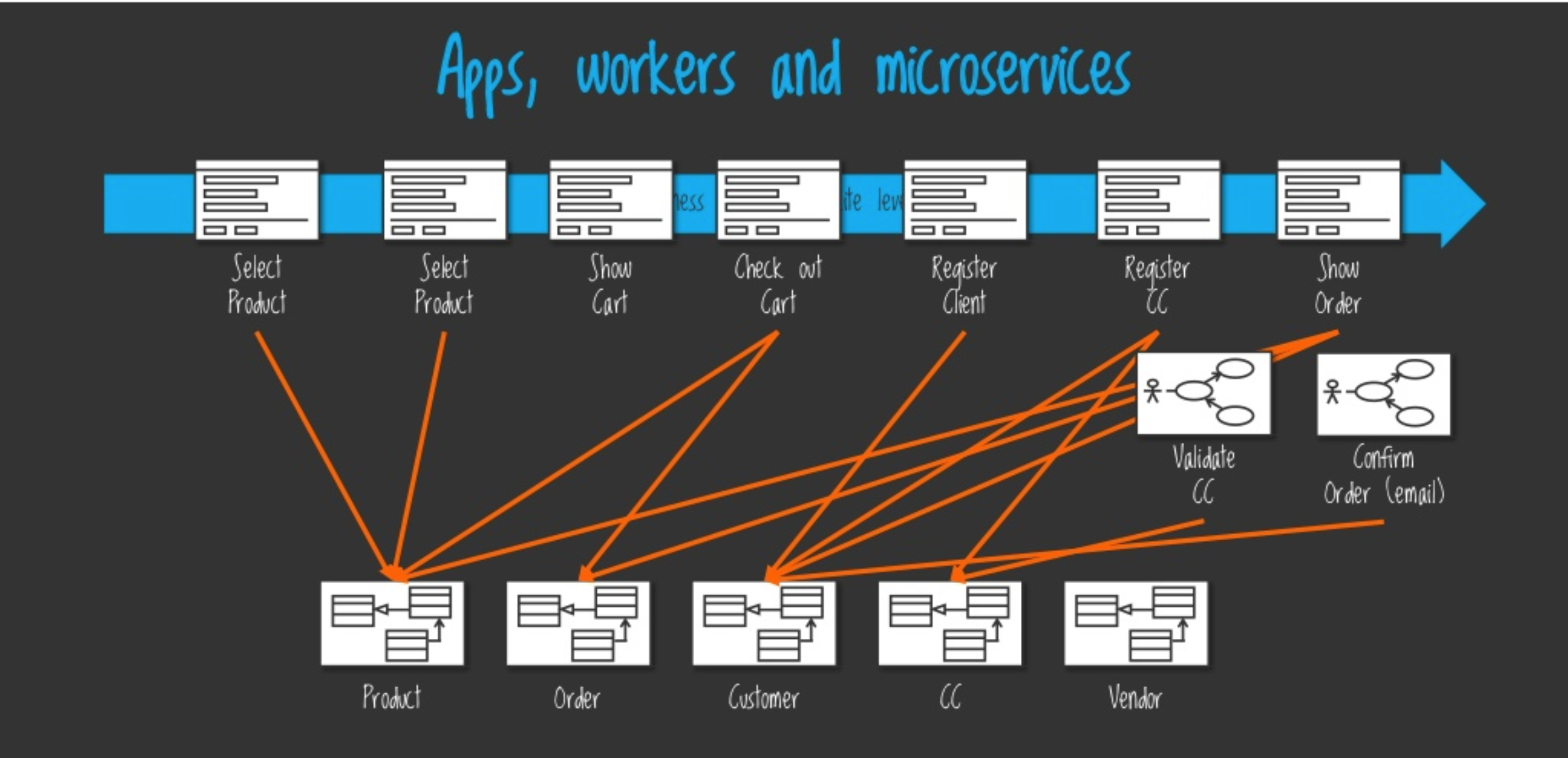

And here we come to the idea of micro-apps. It’s relatively simple – taking the microservices approach and applying it to a frontend application. So we want to split our frontend monolith into many different apps, each of them running in a separate process and communicating to other apps, let’s say, by the HTTP protocol. Here is how the frontend architecture will look like then:

As you see on the slide, our frontend flow has multiple “steps” and each step we consider as a micro-app. We have already defined that, with the micro-apps approach, we’ll have a number of positive effects to the architecture, but how can we actually implement it? Clearly, it’s something new for us, so probably we’ll face some challenges. Let’s look more precisely at what difficulties will appear with the new strategy and what options web developers have.

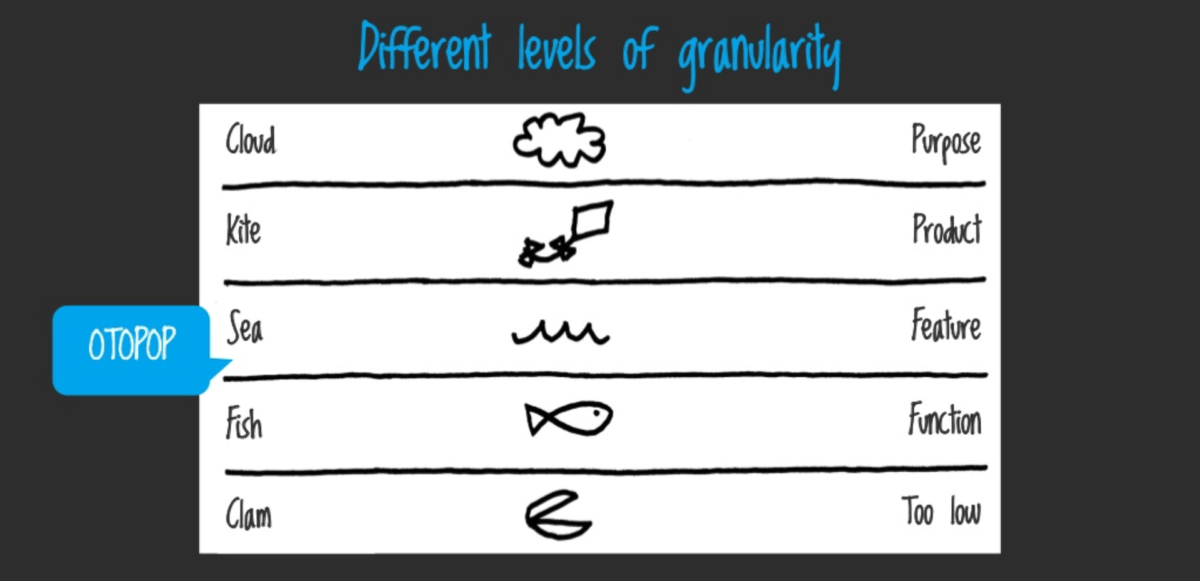

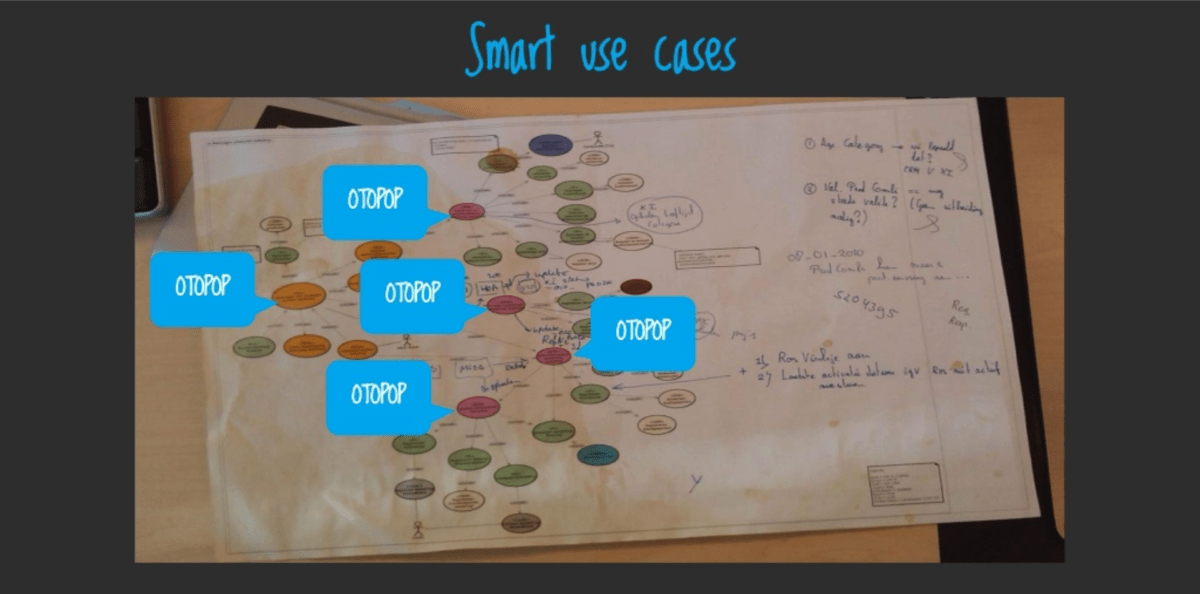

The main question is quite obvious and wide: how to break up the monolith and what architecture should be in our micro-applications? According to the concept of micro-apps, there are different levels of granularity:

Following the idea, a monolith should be split by the middle level of granularity, so-called OTOPOP (One Time, One Place, One Person). This level defines features and it’s exactly what we need. Each application’s feature will become a separate micro-application.

Now let’s see how we going to split the micro-app, what its high-level architecture will look like. Here are key parts of the architecture:

- User interface (pages, web components, grids, panels, controls)

- Process (use cases, flow)

- Domain (factories, repositories, entities, enums, value objects)

- Data/services (gateways)

As you probably noticed, storage is missing in the list. The reason is that this approach considers any storage to live in the “outside” world. A micro-application doesn’t store any data and it’s a key difference if we compare it to a microservice.

DDD and Bounded Context

Before we go further we should recall about DDD (Domain-Driven Design). It’s becoming a more and more common architecture design in modern large web applications these days. In simple terms, its idea is to break down an application into different domains, that are isolated from each other (even if they live within the same codebase).

Bounded Context is a core principle of DDD.

Martin Fowler, the author of Domain-Driven Design, defines it in this way:

Bounded Context is a central pattern in Domain-Driven Design. It is the focus of DDD’s strategic design section which is all about dealing with large models and teams. DDD deals with large models by dividing them into different Bounded Contexts and being explicit about their interrelationships.

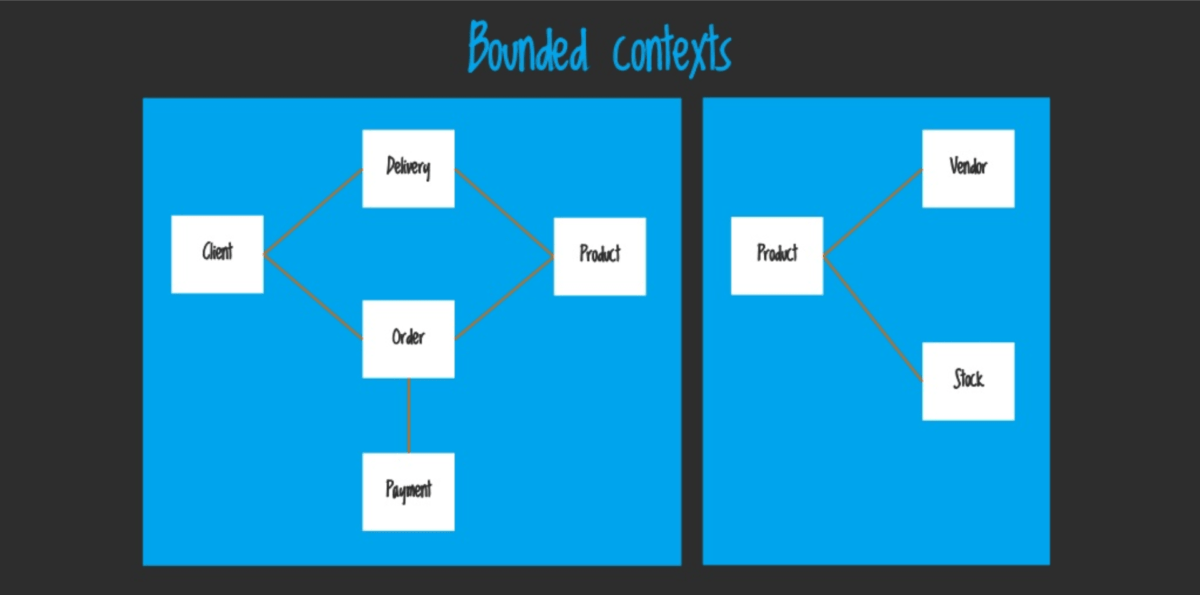

In our case, we can also use DDD and the concept of Bounded Context to split up the large models. It may look like this:

Actually, Domain-Driven Design is a big topic. It requires sufficient knowledge and experience in large projects from developers learning DDD to fully understand it. Also, considering that it’s still quite a new idea to developers and even architects, we are all on a learning curve at the moment. It will take some time to understand the idea, work out the right patterns and apply them to real projects. But it might be the beginning of something great and change how we architect our frontend applications for the next decade. Right now it’s time to analyse this approach and try it out, we definitely can learn something from it.