When thinking about blockchain business use cases, the first thing that comes into every involved actor’s mind is Bitcoin, ancestor and father of all the cryptocurrencies in circulation nowadays.

But blockchain technology does not only imply a new way of generating and performing transactions with virtual money.

At Codemotion Rome 2019, Rossella de Gaetano, Senior Technical Staff Member at IBM and Architect of IBM Cloud, proposed three blockchain business case scenarios where this technology did not involve only money transactions, aiming to clarify this common misconception, highlighting project-related and market-related benefits of involving such a disruptive technology in specific industrial processes.

Blockchain: business scenarios and practical use cases

To succeed, any project involving non-negligible investments involved has to deal with the harsh market rules that govern today’s society.

In the case of proposed use case scenarios, Rossella introduced the Blockchain Business Network, a concept that can be simply divided into:

- Public Network: a defined blockchain network/ledger that can be accessed by anyone, where there is no guarantee related to the identity of involved actors (e.g. Bitcoin or any other cryptocurrency blockchain ledger, 1 click 1 wallet)

- Private Network: a defined blockchain network in which multiple degrees of permission visibility exist over the information available in the chain, and within which all assets get defined properties and any actors involved can prove authentication of their identity

IBM Food Trust: another blockchain business use case

IBM Food Trust is a blockchain-based solution to keep trace of every hop that intercedes the place where producers grow food up to the end stage when the food in question is bought by the consumer.

The Key Business Network features in this solution are Assets definition rules, using smart contracts (a reasonable and elastic solution, since it is tough to define a ship cargo with a hash) and Identity authentication using PKI to ensure confidentiality and non-repudiation between the two involved actors during that part of the food supply chain process.

Eventual contentious activity that needs legal evidence or documentation is solved by keeping a document sharing system detached from the chain where it can physically store copies of the document that certifies a transaction or whatever. n the meantime, the hash fingerprint gets uploaded into the blockchain to certify the authenticity of the document in case anyone with the right to do so can just download it, calculate the hash and, if it matches with the one uploaded into the blockchain, the actor knows that he is reading the correct document.

This solution was designed after an Escherichia Coli bacteria contamination into lettuce spread from Walmart into the USA. It took more than two weeks of investigation due to the multitude of actors involved in the chain before the cause was found. IBM cooperated for more than a year with the supermarket franchise to develop a solution to speed up this process. Simulating the same scenario, it would take two seconds to solve the same issue.

Sovrin, a new frontier for Digital Identity

Sovrin Foundation is a private organisation which aims to govern the world’s first self-sovereign identity (SSI) network. It is another example of a great blockchain business use case.

To ensure the digital identity over the internet, the PKI scheme works pretty well but relies on single points of failure in cases of certificate theft.

One problem with this centralised solution is that we have a single point of failure for the whole CA tree, which is represented by the root CAs (there are around 100 CAs roots worldwide, which have mostly different but some crossed branches between them), so a compromise of one of these represents potential identity compromise for the whole certification tree managed.

Furthermore, certificates are a very valuable asset (think about your passport or a valid signed digital certificate that you own on the same level as the passport that, if stolen, someone else is able to impersonate you through the internet), and so need to be well-defended (both in terms of IT security and physical security access controls). This is why the only ones who require a trustworthy certificate are generally companies, not individual entities.

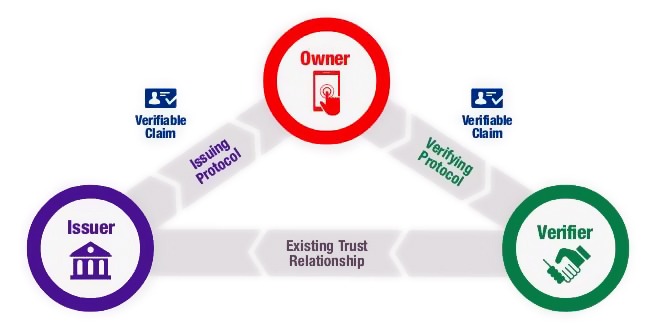

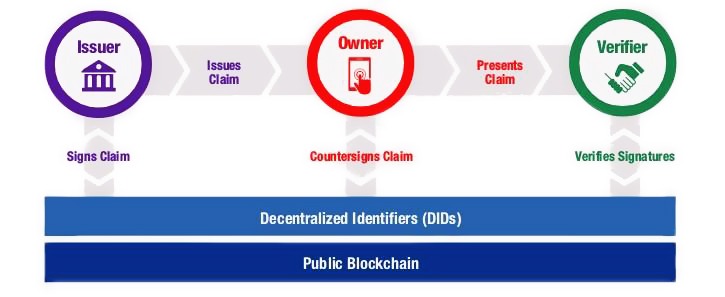

Sovrin tried to solve these issues not by reinventing the wheel but instead merging this centralised but solid solution with the distributed concept of blockchain, creating what is called a DPKI (Distributed PKI), which has a drastically different kind of implementation and potential impact on the managing of digital identity.

Regardless of their specific design, all blockchains represent a cryptographic triple play:

- Each transaction in the blockchain is digitally signed by the originator

- Each transaction—singularly or in blocks—is chained to the prior via a digital hash

- Validated transactions are replicated across all machines using a consensus algorithm

The result is a cryptographic ledger of immutable records that makes it very difficult, if not almost impossible, to change past transactions or maliciously control future ones.

Since every transaction in a blockchain has a digital signature that requires a private key, it is an obvious choice to use the blockchain itself for the storage of the associated public key—or any other cryptographic key over which the key owner needs to prove ownership. This is the core idea behind moving from centralised PKI to DPKI.

In fact, with blockchains, every public key can now have its own address, which is the DID (Digital Identifier) highlighted in the image above.

A DID is stored on a blockchain along with a DID document containing the public key for the DID, any other public credentials the identity owner wishes to disclose and the network addresses for interaction. The identity owner controls the DID document by controlling the associated private key.

This represents a new open standard, a point of change in digital identity, because for the first time in history an identity owner is no longer dependent on an external provider to gain the power of a non- repudiable identifier that can be used over the Internet.

IBM World Wire, because money matters…

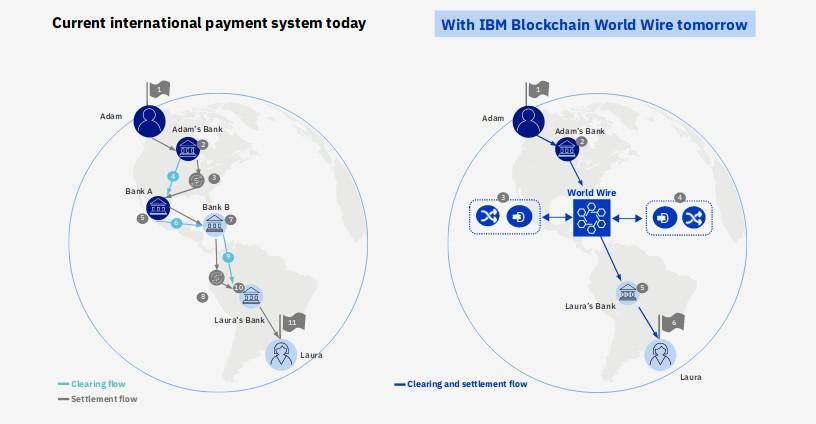

What goes around comes around and, in the end, even IBM implemented its blockchain business solution as an assisting tool between financial institutions’ transaction systems.

As can be shown in the picture, to finalise a transaction between different individuals that retain assets in different financial institutions, a series of in-transaction hops need to be performed (number may vary depending on internal policies and partnerships between individual financial institutions, law related restrictions and so on).

The solution uses digital assets to settle transactions — serving as an agreed-upon store of value exchanged between parties — as well as integrating payment instruction messages. It means funds can now be transferred at a fraction of the cost and time of traditional correspondent banking.

The process of transferring money from Alice to Bob can be described this way:

- Alice wants to send money to Bob and uses its financial institution as a pivot for such operation

- Alice and Bob financial institutions transacting together agree to use a stable coin, central bank digital currency or other digital asset as the bridge asset between any two fiat currencies.

- The institutions use their existing payment systems – seamlessly connected to World Wire’s APIs – to convert the first fiat currency into the digital asset.

- World Wire then simultaneously converts the digital asset into the second fiat currency, completing the transaction, writing it into the blockchain.