The advent of agile methodologies has certainly been a phenomenon similar to the revolution of the 1960s. I believe that it’s some sort of Woodstock of information, which, as often happens in life, I only saw from afar.

However, I continue to meet people who were there and who always stop to tell me that such an event will never happen again and how the programmers of the past loved each other, exchanged flower crowns, etc. Well, in short, the Robert Downey Jr. meme fits perfectly.

My historical legacy as a consultant has taught me that talking about Agile in Public Administration contexts puts the entire department in a bad mood where you should work and makes you seem like one of those characters ready to be stoned in Brian of Nazareth.

On the contrary, in startup contexts, showing a Gantt chart causes narcolepsy and dizziness in many boards, especially if there are some hotheads.

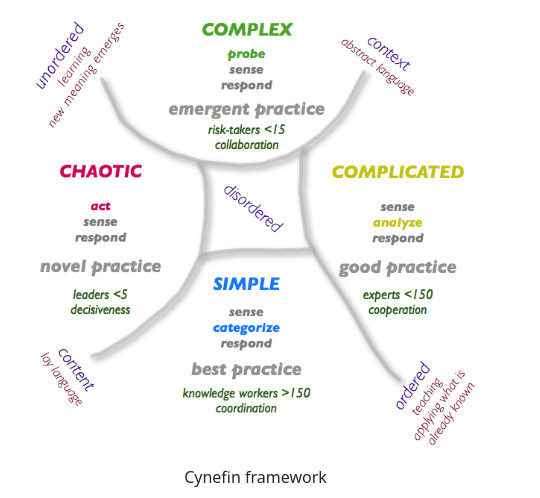

However, the non-orthodox know that both can be applied in contexts where Cynefin allows us to frame the problem in terms of complexity, chaos, simple, and complicated.

But once an agile path is taken, you begin to evaluate which framework to choose, and there begins another war, smaller but no less bloody.

Did Scrum come before Agile, or Agile before Scrum? Although the Scrum methodology is an agile framework, its primordial form was first introduced by Jeff Sutherland, John Scumniotales, and Jeff McKenna in 1986 at the consulting company “Easel Corporation.” Initially, the term “Scrum” was borrowed from the context of rugby to describe a collaborative way of playing, echoing the actions of the scrum.

In 1991, Jeff Sutherland presented Scrum at the OOPSLA conference (Object-Oriented Programming, Systems, Languages & Applications), contributing to formalizing the concepts of Scrum. During this period, Ken Schwaber was independently working on iterative development methods and joined Sutherland to extend and promote Scrum. In 1995, Schwaber and Sutherland published the first article on the Scrum Development Process. During this period, they began to define key roles in Scrum, such as Product Owner, Scrum Master, and Development Team, along with events like Sprint and Sprint Review.

“If we interview 3 Scrum experts, they would describe it so differently that it would seem like being in a famous Kurosawa movie.”

In 2001, Schwaber was involved in drafting the Agile Manifesto in Snowbird, Utah, which emphasizes the fundamental principles of agile approaches in software development. As can be read on the page that recalls the event, Scrum was one of the key frameworks mentioned in the Agile Manifesto.

In 2009, Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland published the first version of the “Scrum Guide,” a document that clearly and concisely defines the roles, events, and artifacts of Scrum. The Scrum Guide has become the official resource for understanding Scrum.

Scrum has gained popularity beyond software development, extending to other disciplines such as project management, product management, and even marketing, but some even use it for cooking. Its application has spread to various sectors beyond the technological one, and today Scrum is one of the most used agile frameworks, offering a flexible and collaborative approach to product development and project management. The Scrum Guide is periodically revised to reflect emerging best practices and keep Scrum updated.

But what is the Scrum methodology? If we interview 3 Scrum experts, they would describe it so differently that it would seem like being in a famous Kurosawa movie, so let’s put all the disclaimers in the world on what follows. Even the description given by scrum.org states that Scrum “helps people and teams deliver value incrementally in a collaborative way. As an agile framework, Scrum provides enough structure to allow people and teams to integrate the way they work, while also adding the right practices to optimize their specific needs.” It starts with the laconic phrase “If you’re starting with Scrum, think of it as…” meaning the journey is better than the destination, and you’re just beginning.

In practice, it provides a structure for collaborative work within projects (complex ones). It is designed to enable rapid development and delivery of quality products, focusing on flexibility and responding to customer or market needs. So it is:

Iterative and incremental: Scrum organizes work into iterations called sprints, each usually lasting from one to four weeks. During each sprint, a product increment is produced.

Defined roles: Scrum clearly defines the main roles, including the Product Owner (responsible for the product), the Scrum Master (process facilitator), and the Development Team. Each role has specific responsibilities.

Product backlog: The Product Owner maintains a backlog of products, a prioritized list of work items representing desired features or goals for the final product.

Sprint planning and Scrum meetings: At the beginning of each sprint, the team meets to plan which backlog items will be completed during the iteration. At the end of each day, a short meeting called Scrum daily is held to monitor progress and identify any obstacles. To date, the bloodiest events after condo meetings.

Review and retrospective: At the end of each sprint, the team holds a review to demonstrate the results achieved during the sprint and review the backlog. Subsequently, a retrospective is held to reflect on the team’s performance and identify improvements for the next sprints. Here, the infamous “team velocity” is also measured.

Regular transparency and inspection: Scrum is synonymous with transparency. Through tools like the backlog and the burndown chart, it allows constant inspection of progress and course correction, if necessary.

Adaptability: Scrum is designed to adapt to changes in product requirements or customer priorities. Adaptability is built into the framework, allowing the team to promptly respond to feedback and requested changes. Usually in these contexts, the least adaptable turns out to be the scrum master.

Why Scrum Methodology Sucks

Opinions on Scrum, or any framework or methodology, vary depending on personal experiences, project needs, and the team at hand.

Many people find that the Scrum methodology does not fit well into their context or that there are specific challenges in implementing it, but this is the first ‘conservative’ reaction of any company facing a novelty, and we know after numerous studies and as many memes that the most dangerous phrase in modern economy is “we’ve always done it this way.”

If we delve a bit deeper, we can find some common criticisms:

Complexity: Many argue that Scrum can seem complicated and require a considerable learning curve to be implemented correctly. Clearly, this depends a lot on who has tried to implement Scrum in the company.

As we know, the road to hell is paved with good intentions, and if I had a euro for every inexperienced person who tried Scrum in companies, letting it die after a while, now I would have at least the equivalent of a Bitcoin.

Adaptability: Some challenge Scrum’s ability to effectively adapt to all types of projects, especially those of small size or highly complex. Personally, it works very well for small ones, but for highly complex ones, I can’t vouch for it because I’ve never sent rockets to the moon (yet).

Focus on the quantity of work: More than once, many complained that the focus on sprints and planning based on the quantity of work (estimation of story points) led to a lack of attention to the quality of the product. And unfortunately, I have experienced this several times. The team is made up of people (for now 😄), and people, depending on their seniority, ignore that the qualitative aspect should never be overlooked. A cultural problem that is at the root of the failure of Scrum adoption in almost all contexts.

Rigid roles: Some teams may find that Scrum’s rigid role structure (Scrum Master, Product Owner, Team) may not adapt well to their corporate culture or team dynamics. Again, it’s not the rigidity of Scrum, let’s remember it’s a framework, rather the rigidity of people that makes it seem less adaptable in unconventional contexts.

Difficult cultural changes: Implementing Scrum may require significant cultural changes within an organization, and people may resist such changes. I believe this is the main issue. It is not possible to adopt Scrum where there is cultural resistance to change and people do not fully understand the benefits of such a change. Not only do you risk failing to implement the framework, but you may even come out much less convinced that Scrum can be the solution to many problems, making us unsure of its adaptability.

Almost all criticisms of Scrum stem from incorrect interpretations or implementations, rather than intrinsic flaws in the framework. Many organizations find Scrum extremely useful for improving transparency, communication, and value delivery.

As with any methodology, it is important to adapt and customize Scrum based on the specific needs of the team and the project. But above all, it is always better to test the organization’s willingness to change.